Posted On: May 15, 2020 by Community HealthCare System in: Community health news News

Healthcare organizations have learned many grim lessons from both natural and human-made disasters in the last two decades. 9/11, an Ebola outbreak, Hurricane Katrina, mass shootings, and more have raised awareness of the need to prepare for the worst. But preparation can’t happen in a vacuum, and no one organization can cover every possible set of circumstances.

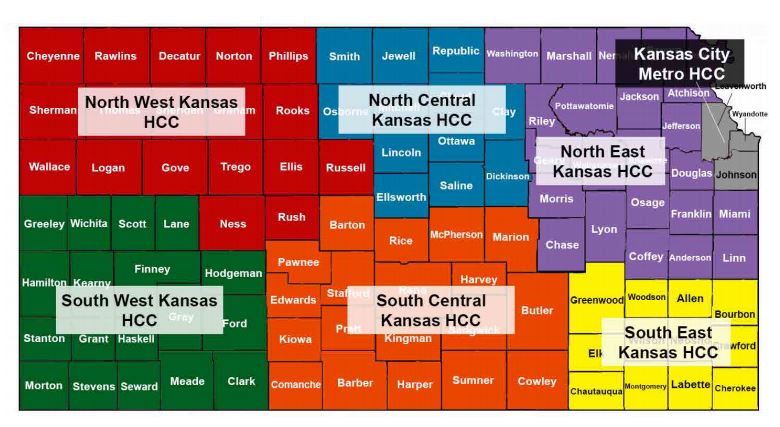

Healthcare coalitions aim to help the many contributors to a region’s preparedness break down barriers and increase overall emergency preparedness and response capabilities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Northeast Kansas Healthcare Coalition has done just that.

Representatives from the Coalition’s Core members (Hospitals, Emergency Medical Services, Emergency Management, Public Health) and more have come together to share knowledge, best practices, and even supplies to ensure that our region stands ready for COVID-19. The Coalition covers 23 counties and represents more than 50 organizations. Lawrence Memorial Hospital and Community HealthCare System are co-lead hospitals.

According to Michael Bomberger, director of business development and special projects at Community HealthCare System and Coalition chair, situational awareness and information flow are important, but relationships are key.

“When I pick up the phone today and call someone from whatever realm—public health or emergency management, for example—they know who I am and what I do. It’s trust: We already trust each other because we’ve developed relationships during times of relative calm,” Bomberger said.

Healthcare coalitions were established with that trust in mind. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response established the present program in 2006 and offered grants to develop a healthcare emergency system. In Kansas, the Kansas Department of Health and Environment contracts with Healthcare Coalition Partners of Kansas, co-owned by Coalition Readiness and Response Coordinators Danielle Marten and Tami Wood, to coordinate deliverables. Marten said because healthcare is doing “more with less” and closely evaluating financials, it isn’t always able to sink time and resources into preparedness.

“That’s the beautiful benefit of the coalition: You know a little bit, I know a little bit, and we can share and leverage each other’s knowledge and experience and become more prepared for an emergency than we ever would by ourselves with the amount of time we have in a day,” Marten said.

Marten said previous drills, including a past exercise with measles, a highly infectious disease, have helped organizations know how to react. “The number one benefit is the ability to pass along reliable information through different disciplines of healthcare,” she said.

“If you’re the EMS provider, you know how to protect yourself and get the patient to a critical access hospital, and the critical access hospital has received the same training and information, and it’s the same as those [where the patient may transfer to] at larger hospitals,” Marten said.

Competition for patients can sometimes complicate collaborative efforts, but Andrew Adams, public health emergency preparedness coordinator for the Riley County Health Department and vice chair of the Coalition, said the Coalition has been able to help break down barriers by facilitating participation from many provider types such as long-term care facilities, dialysis centers, and surgical centers in addition to core members.

“We’ve been able to share ideas, shortcomings, and successes freely and openly, even when other providers who are ‘competition’ in the same marketplace are in the room. When we meet as a Coalition, we’re able to put aside corporate needs/rivalries and focus on the greater good of the community,” Adams said.

The “whole community” approach to preparedness has paid dividends during the pandemic. According to Dr. Lillian Lockwood, emergency medicine physician and co-clinical advisor for the Coalition, the group has provided shared informational resources, including learning opportunities and planning strategies, and distributed much-needed supplies and decontamination equipment. Coalition leadership recently participated in a panel discussion about supply-chain difficulties for Kansas State University students in Industrial and Manufacturing Systems Engineering. The virtual session was also open to the public. Weekly webinars for Coalition members help everyone learn the latest clinical information.

Dr. Lockwood provided a 30-minute webinar for members in early April that included crucial updates on treating patients with COVID-19. She discussed symptoms patients present with and how to manage ventilators and other resources to support the best outcomes for patients. For example, some COVID-19 patients struggle to breathe, whereas others have low oxygen levels but do not have other symptoms consistent with respiratory failure.

The range of patient symptoms requires broad preparation and demonstrates the complicated nature of the problems that need to be solved.

“The COVID pandemic has been a very fluid event. The severity has reinforced the importance of collaboration. As demonstrated in hard-hit areas like New York, it is essential for effective disaster response to include all interested parties invested in the care of our communities,” Dr. Lockwood said.

In addition to sharing subject matter and clinical expertise, the Coalition has worked to distribute necessary supplies. The Coalition issued N95 masks, surgical masks, and gowns to hospitals, public health departments, and other institutions across 18 counties in March and April. Another crucial acquisition was a SteraMist system that can be shared among facilities and used to decontaminate personal protective equipment, or PPE, patient rooms, ambulances, and more.

Steve Land, administrator of Wamego Health Center, said he has “sincerely appreciated the collaboration” during the pandemic. When the Coalition secured single-use ventilators, he expressed his gratitude and said his providers “were very appreciative to have this capacity within our facility during potential transfers.”

Adams said supplies have emerged as one of the greatest preparedness gaps “not only in our region or state, but nationwide and globally.” Jeremy Brandt, physician assistant for Community HealthCare System and co-clinical advisor for the Coalition, said helping provide PPE made a real impact in helping the region and Coalition members. But both Adams and Brandt find the greatest value in ongoing preparedness efforts.

“There are people who are thinking about emergency preparedness all year long, not just when it comes up. That doesn’t make us experts in everything, but having thoughtfulness in that realm is valuable,” Brandt said.

Adams agreed, noting that the Coalition engages in a cycle of planning, training, and evaluating by conducting exercises and drills. Now that everyone is living through a pandemic, the idea of continuous improvement is even more important.

“There will never be a steady state, or a time where we can say ‘we’re prepared.’ Preparedness is a continuous effort,” Adams said.

Seeing how Coalition efforts have helped is keeping members motivated to press on.

“I feel fortunate to be in a role where I can have some input and help this sort of effort through planning and helping through tough times like this,” Brandt said.

Bomberger noted that the Coalition works to be a bridge that connects community resilience efforts and creates infrastructure for collaborative response to and recovery from catastrophic events. The Coalition itself gains valuable insight from many disciplines and individuals, including Angela Krutsinger, Region VII field project officer, HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response; Kendra Baldridge, Director of the Bureau of Community Health Systems at the Kansas Department of Health & Environment; Denise Kelly, Director of the Preparedness Program at the Kansas Department of Health & Environment; and partners like Ron Marshall, Director of Preparedness and Regulatory Affairs at the Kansas Hospital Association.

These ongoing interactions and deliberations have been invaluable.

“The problem-solving and information-sharing between the region’s cooperative network of dedicated healthcare professionals has undoubtedly benefited our communities,” Dr. Lockwood said.

Northeast Kansas Healthcare Coalition leaders (from left) Danielle Marten, Dr. Lillian Lockwood, and Michael Bomberger provided 540 Stop the Bleed Kits to organizations in 14 different counties last fall. Distribution of the kits enabled training of 1,700 citizens on how to take quick action to stop severe bleeding and save lives during a traumatic event. The Coalition has provided crucial training and personal protective equipment to the region to prepare for and protect against COVID-19.

Healthcare Coalitions serve the entire state of Kansas. Find more information at https://www.kshcc.com/.

0 comments